Intellectual Output of SIC first workshop

Nov. 24 to 28, 2016, Novo Mesto (Slovenia)

Were you ever interested in what the difference in terms between a refugee and a migrant actually is? What about the history of migrations and the current situation in that area? Statistics indeed show that, on a personal level, people are surprisingly ready to do a lot for the integration and acceptance of refugees and migrants, which is often not reflected in policies and measures of nation states.

Picture with courtesy of Snježana BLAGOJEVIC

1 VOCABULARY

2 HISTORY OF MIGRATIONS

2.1 1800s to 1930s: Migrations to the New world

2.2 Late 1940s to 1960s: Migrations post World War II

2.3 Migrations post 1970s

3 REFUGEE CRISIS (2006 AND LATER IN EUROPE)

4 GOOD PRACTICES (GOVERNMENTAL AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS)

5 INTEGRATION PROGRAMMES (BENEFICIARIES OF INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION)

6 SITUATION IN SLOVENIA DURING THE REFUGEE CRISIS

7 RIGHTS OF ASYLUM SEEKERS AND RECOGNIZED INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION IN SLOVENIA

8 REFUGEE WELCOME SURVEY

9 STATISTICS

Definitions important to know about migrations and refugees.

Assisted Voluntary Return – Administrative, logistical, financial and reintegrational support to rejected asylum seekers, victims of trafficking in human beings, stranded migrants, qualified nationals and other migrants unable or unwilling to remain in the host country who volunteer to return to their countries of origin.

Asylum seeker – A person who seeks safety from persecution or serious harm in a country other than his or her own and awaits a decision on the application for refugee status under relevant international and national instruments. In case of a negative decision, the person must leave the country and may be expelled, as may any non-national in an irregular or unlawful situation, unless permission to stay is provided on humanitarian or other related grounds.

Border management – Facilitation of authorized flows of persons, including business people, tourists, migrants and refugees, across a border and the detection and prevention of irregular entry of non-nationals into a given country. Measures to manage borders include the imposition by States of visa requirements, carrier sanctions against transportation companies bringing irregular migrants to the territory, and interdiction at sea. International standards require balancing between facilitating the entry of legitimate travellers and preventing entry of travellers arriving for inappropriate reasons or with invalid documentation.

Circular migration – The fluid movement of people between countries, including temporary or long-term movement which may be beneficial to all involved, if occurring voluntarily and linked to the labour needs of countries of origin and destination.

Country of origin – The country that is a source of migratory flows (regular or irregular).

Emigration – The act of departing or exiting from one State with a view to settling in another.

Facilitated migration – Fostering or encouraging regular migration by making travel easier and more convenient. This may take the form of a streamlined visa application process, or efficient and well-staffed passenger inspection procedures.

Forced migration – A migratory movement in which an element of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood, whether arising from natural or man-made causes (e.g. movements of refugees and internally displaced persons as well as people displaced by natural or environmental disasters, chemical or nuclear disasters, famine, or development projects).

Freedom of movement – A human right comprising three basic elements: freedom of movement within the territory of a country (Art. 13(1), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948: “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.”), the right to leave any country and the right to return to his or her own country (Art. 13(2), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948: « Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.’’ See also Art. 12, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Freedom of movement is also referred to in the context of freedom of movement arrangements between States at the regional level (e.g. European Union).

Immigration – A process by which non-nationals move into a country for the purpose of settlement.

Internally Displaced Person (IDP) – Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border (Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, UN Doc E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2.). See also de facto refugees, displaced person, externally displaced persons, uprooted people.

International minimum standards – The doctrine under which non-nationals benefit from a group of rights directly determined by public international law, independently of rights internally determined by the State in which the non-national finds him or herself. A State is required to observe minimum standards set by international law with respect to treatment of non-nationals present on its territory (or the property of such persons), (e.g. denial of justice, unwarranted delay or obstruction of access to courts are in breach of international minimum standards required by international law). In some cases, the level of protection guaranteed by the international minimum standard may be superior to that standard which the State grants its own nationals.

Irregular migration – Movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries. There is no clear or universally accepted definition of irregular migration. From the perspective of destination countries it is entry, stay or work in a country without the necessary authorization or documents required under immigration regulations. From the perspective of the sending country, the irregularity is for example seen in cases in which a person crosses an international boundary without a valid passport or travel document or does not fulfil the administrative requirements for leaving the country. There is, however, a tendency to restrict the use of the term « illegal migration » to cases of smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons.

Labour migration – Movement of persons from one State to another, or within their own country of residence, for the purpose of employment. Labour migration is addressed by most States in their migration laws. In addition, some States take an active role in regulating outward labour migration and seeking opportunities for their nationals abroad.

Migrant – International Organization for Migration defines a migrant as any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is. IOM concerns itself with migrants and migration‐related issues and, in agreement with relevant States, with migrants who are in need of international migration services.

Migration – The movement of a person or a group of persons, either across an international border, or within a State. It is a population movement, encompassing any kind of movement of people, whatever its length, composition and causes; it includes migration of refugees, displaced persons, economic migrants, and persons moving for other purposes, including family reunification.

Migration management – A term used to encompass numerous governmental functions within a national system for the orderly and humane management for cross-border migration, particularly managing the entry and presence of foreigners within the borders of the State and the protection of refugees and others in need of protection. It refers to a planned approach to the development of policy, legislative and administrative responses to key migration issues.

Naturalization – Granting by a State of its nationality to a non-national through a formal act on the application of the individual concerned. International law does not provide detailed rules for naturalization, but it recognizes the competence of every State to naturalize those who are not its nationals and who apply to become its nationals.

Push-pull factors – Migration is often analysed in terms of the « push-pull model », which looks at the push factors, which drive people to leave their country (such as economic, social, or political problems) and the pull factors attracting them to the country of destination.

Receiving country – Country of destination or a third country. In the case of return or repatriation, also the country of origin. Country that has accepted to receive a certain number of refugees and migrants on a yearly basis by presidential, ministerial or parliamentary decision.

Refugee – A person who, « owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinions, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country. (Art. 1(A)(2), Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, Art. 1A(2), 1951 as modified by the 1967 Protocol). In addition to the refugee definition in the 1951 Refugee Convention, Art. 1(2), 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention defines a refugee as any person compelled to leave his or her country « owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country or origin or nationality. » Similarly, the 1984 Cartagena Declaration states that refugees also include persons who flee their country « because their lives, security or freedom have been threatened by generalised violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violations of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order. »

Repatriation – The personal right of a refugee, prisoner of war or a civil detainee to return to his or her country of nationality under specific conditions laid down in various international instruments (Geneva Conventions, 1949 and Protocols, 1977, the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Annexed to the Fourth Hague Convention, 1907, human rights instruments as well as customary international law). The option of repatriation is bestowed upon the individual personally and not upon the detaining power. In the law of international armed conflict, repatriation also entails the obligation of the detaining power to release eligible persons (soldiers and civilians) and the duty of the country of origin to receive its own nationals at the end of hostilities. Even if treaty law does not contain a general rule on this point, it is today readily accepted that the repatriation of prisoners of war and civil detainees has been consented to implicitly by the interested parties. Repatriation as a term also applies to diplomatic envoys and international officials in time of international crisis as well as expatriates and migrants.

Resettlement – The relocation and integration of people (refugees, internally displaced persons, etc.) into another geographical area and environment, usually in a third country. In the refugee context, the transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought refuge to another State that has agreed to admit them. The refugees will usually be granted asylum or some other form of long-term resident rights and, in many cases, will have the opportunity to become naturalized.

Smuggling – « The procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident” (Art. 3(a), UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000). Smuggling, contrary to trafficking, does not require an element of exploitation, coercion, or violation of human rights.

Stateless person – A person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law » (Art. 1, UN Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, 1954). As such, a stateless person lacks those rights attributable to national and diplomatic protection of a State, no inherent right of sojourn in the State of residence and no right of return in case he or she travels.

Trafficking in persons – « The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation » (Art. 3(a), UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000). Trafficking in persons can take place within the borders of one State or may have a transnational character.

Xenophobia – At the international level, no universally accepted definition of xenophobia exists, though it can be described as attitudes, prejudices and behaviour that reject, exclude and often vilify persons, based on the perception that they are outsiders or foreigners to the community, society or national identity. There is a close link between racism and xenophobia, two terms that can be hard to differentiate from each other.

Retour en haut

2 HISTORY OF MIGRATIONS

2.1 1800s to 1930s: Migrations to the New world

This time is linked with the rise of industrial power of the USA and industrialization of Australia and New Zealand. This migration flow is due to escaping poverty and politically repressive regimes in migrants’ home countries in Europe. Their motivation was the prospect of economic opportunity in the USA and the former colonies in the New World.

The number of migrants who left Europe between 1800 and 1930 is approximately 48 million (Massey et al., 1998). This number consists of 8 million migrants from British Isles, including more than 1 million people from Ireland, who left because of potato famine in 1845-47. The New Zealand and Australian government continued to offer assisted passages to migrants from Europe.

Retour en haut

2.2 Late 1940s to 1960s: Migrations post World War II

Migrations in this period were defined by reconstruction efforts in Europe and the economic boom in Europe, North America and Australia. Migrants from Turkey came to find work in Germany, those from former French colonies in North Africa came to find work in France and those from former colonies in the Caribbean and South Asia came to find work in Britain.

Labour migrations from Britain to Australia were perceived as permanent, because Australian government granted every migrant £10 (“ten pound poms”). Germany also gave migrants from Turkey visas as “guest workers.” Many of migrants in this period of time permanently moved to receiving countries.

Retour en haut

2.3 Migrations post 1970

From 1970s the variation of sending and receiving countries has grown phenomenally. Countries like the USA, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand were joined by Italy, Spain and Portugal, the countries that used to be emigration countries. The escalation of oil price led to the economic boom in the Persian gulf, which led to massive labour immigrations to those countries. People also migrated because of labour to newly industrialized countries in Asia, such as Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Singapore. These migrations werent usually permanent. Features of this period of migration are different than the periods before. According to the UN, the proportion of women migrants has increased over the years. Nearly half of the world´s migrants in 2005 were women. Some countries noted more female than male migrants (Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, North America, Oceania and the former USSR – Koser, 2007:6). Reasons for women migration in the earlier period were joining their partner or families or travelling together, but nowadays an increasing number of women migrate independently. More migrations are becoming temporary and circular nowadays and people are more likely to move to different countries more than once and to return to their home country.

Retour en haut

3 REFUGEE CRISIS (2006 AND LATER IN EUROPE)

For the last ten years an increasing number of people began departing North Africa (mostly people from Lybia trying to reach Italy) to reach Europe. This will be described in the chapter on the refugee crisis. These people were often victims of people smugglers, who frequently put large numbers of refugees and migrants in unsafe boats, without safety equipment, food or water and sometimes even without enough fuel to complete the crossing of the sea. The numbers are horrifying, and while thousands of people did reach Italy, but what about people who drowned in the sea or died in other ways on the path to a better future. In 2013 Italy established a search and rescue operation called Mare Nostrum, following shipwrecks near the island of Lampedus, leading to a smaller operation called Triton after hundreds of people drowned, including children. The operation Mare Nostrum was replaced and refocused on patrolling borders close to land and no more in the open sea. The results were more people being found dead by drowning. After one weekend in mid April 2015, when more than one thousand refugees and migrants died in a series of incidents off the Lybian coast, EU leaders decided to expand the operation Triton and EU countries dispatched naval vessels to the region.

Since the start of the Syrian crisis thousands of refugees have tried to reach Europe using different routes other than the Mediterranian sea, e. g. via Turkey to Bulgaria or via Turkey across the Aegean sea to Greece. In 2015, 800.000 and more people, mostly refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Eritrea, Somalia and Iraq, crossed from Turkey to Greece. The overwhelmed reception system of registration in Greece failed and hundreds of thousand refugees and migrants left the country and marched on through the Balkans. For the most of them the aim was Germany. The results were devestating. Some Balkan countries closed their borders, others ushered refugees and migrants through. People were forced to sleep outside in cold weather and bad conditions. Some countries provided adequate shelters.

In 2014, 563.000 people applied for asylum in the EU. In 2015, the number was 1.26 million, due to the higher numbers of applicants from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. After the Balkan refugee route was closed, 46.000 of refugees and migrants got stuck in Greece in very poor living conditons.

The responses of governments to humanitarian and refugee crisis on the Balkan route were: increasing border security in Hungary, Bulgaria; Slovenia, Czech republic and Slovakia; deployment of staff from Poland and Slovakia to other countries to help them protect their borders; lawsuits against the European Union over relocation and resettlement at the European Court of Justice (Hungary, Slovakia), public campaigns against relocation and resettlement (Hungary), restriction of asylum seeker rights (Hungary, Slovakia) and preparation of reception centres and emergency shelters in the case of increased number of arrivals (Slovenia, Romania).

Retour en haut

4 GOOD PRACTICES (GOVERNMENTAL AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS)

Sloga is an NGO coordination in Slovenia, which was established before the refugee and migrant crisis reached Slovenia with the aim of a coordinated NGO response. When the crisis started, this coordination served as the key NGO counterpart in dialogue with the government and remained active even after the closing of the Balkan route by carrying out joint advocacy activities, awareness-raising actions, capacity building activities and exchanging information. Romania established the Government Inter-Ministerial Committee, which is a National Coalition for the integration of refugees; its aim is harmonization of legalisation and coordination between state agencies and NGOs. On a local level there was a mixed response, municipalities near borders who were affected by the refugee flow seemed to have a more tolerant attitude towards migrants. Other municipalities had some protests. Poland adopted an Immigrants Integration Model at the city of Gdansk. In Romania, Bucharest City Hall adopted the Direction for the Integration of Foreigners and Diversity.

Retour en haut

5 INTEGRATION PROGRAMMES (BENEFICIARIES OF INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION)

Poland: programme duration is 12 months, they are given financial aid, language classes and specialized counselling.

Czech republic: programme duration is 6-12 months, they are given financial aid, language classes and accomodation.

Slovakia: provided by NGOs and based on AMIF funding, programme duration is 6 months.

Hungary: no integration programme since 1 June 2016.

Bulgaria: there is no operational integration programme, but there is a pilot UNHCR- funded project.

Romania: programme duration is 12 months, in cooperation with the government and NGOs, they are given financial aid and language classes.

Slovenia: orientation programme duration is 3 months, integration programme duration is up to 3 years (language and civic education and personal integration plan).

Retour en haut

6 SITUATION IN SLOVENIA DURING THE REFUGEE CRISIS

Recent refugee and migrant crisis reached Slovenia in September 2015, when the first group of refugees and migrants arrived. An unprecedented influx of refugees and migrants hit Slovenia as a consequence of Hungary closing its border with Serbia and Croatia. From October 2015 to January 2016, 422.000 refugees and migrants crossed Slovenia, but Slovenia was only a transitional country on their way towards Western European countries. After initial attempts by Slovenian authorities to apply standard border control protocols, Slovenia set up a humanitarian ‘corridor’ (organized transport for the refugees and migrants from Slovenian-Croatian border to Slovenian border with Austria) to enable the migrants safe passage. Migrants and refugees have been registered and were provided with basic care. The government set up reception and accommodation camps in the border areas.

October was marked by a crisis situation as the Government (and other stakeholders) were not prepared for managing unexpected numbers of refugees and migrants, with their number reaching its peak at the end of month with 25,000 refugees and migrants entering Slovenia in one weekend; the Government had troubles with handling the crisis on the operational level. Bilateral tensions arose with Croatia due to the lack of coordinated approach with the Croatian government and police, which led to refugees being stranded in the so called “no man’s land” and/or their attempts to enter Slovenia via the green border. In October, Slovenia (and Croatia) asked the EU for police to help regulate the flow coming from Croatia; they received assistance from 400 policemen from EU member states.

In November 2015, the Government decided to implement “temporary technical obstacles” (razor – wire fence) on the border with Croatia (although even in September, the Government had been critical towards Hungary building the fence on its border). The measure was explained to be aimed at avoiding a « humanitarian disaster », although the number of refugees and migrants was falling after its peak in October, and Austria – the next country along on the migrant route – was planning to restrict the daily number of new arrivals, which could create a backlog in Slovenia. Local inhabitants were mostly opposing the fence, therefore the government removed parts of it soon after its installation and replacing it in some places with panel fences. In November, the Government also passed new amendments to the Defense Law, giving the military broad powers over the civilian population.

As the Government discourse was mostly focusing on the security aspect (refugees and migrants as a threat to national security), the public opinion was not favourable to refugees. Number of self-organized groups, volunteers, and NGOs were providing assistance to the refugees, but their views were not shared by the general public.

In March, Slovenia (with the neighbouring Croatia) announced it will refuse to allow the transit of most refugees through their territory (access only granted to foreigners meeting the requirements to enter the country, those wishing to apply for asylum, and refugees selected on a case by case basis on humanitarian grounds and in accordance with the rules of the Schengen zone) with the aim of shutting down the Balkan route, setting off a domino effect among Balkan states. The announcement followed Austria’s decision in February to cap the number of refugees passing through its territory, and was announced the next day after signing the EU-Turkey deal. The decision of restricting entry to refugees and migrants in Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia and Macedonia caused a bottleneck of 36,000 refugees stuck at the Greek-Macedonian border, unable to continue their journey.

Although the Balkan route is closed, unprecedented numbers of asylum-seekers and refugees represent a challenge for the Government. The crisis strengthened the presence of international organizations in Slovenia. The Government is maintaining three reception/accommodation centres (Dobova, Šentilj, Lendava) on stand-by in case of the increased influx of refugees and migrants to Slovenia repeating itself.

Upon arrival to Slovenia, asylum-seekers are placed in Asylum Home, therefore are spatially isolated, which doesn’t provide a good basis for integration. Language courses are provided already in asylum centers and after granting international protection status. In Autumn of 2015, as an apparent response to the mass transit of refugees, several amendments have been added to the International Protection Act (introduction of border procedures, shortening of the deadline for the legal remedy in accelerated procedures from eight to three days, abolishment of the one-off financial assistance for beneficiaries of international protection, and abolishment of financial compensation for accommodation in a private home for reunited family members of persons with subsidiary protection); amendments were adopted in 2016.

Retour en haut

7 RIGHTS OF ASYLUM SEEKERS AND RECOGNIZED INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION IN SLOVENIA

International protection in Slovenia shall mean refugee status and subsidiary protection status.

Refugee status is granted to a third-country national who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group, is outside the country of nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of that country, or a stateless person who is outside the country of former habitual residence and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it.

Subsidiary protection status is granted to a third-country national or a stateless person who does not qualify for refugee status, but in respect of whom substantive grounds exist to suspect that the person is concerned if returned to his or her country of origin, or in the case of a stateless person, to his or her country of recent habitual residence, would face a real risk of serious harm.

The competent authority shall establish the grounds for granting international protection in a uniform procedure, whereby it shall first examine the conditions for granting refugee status and only then, if these are not met, the conditions for granting a subsidiary form of protection.

Subsidiary protection status is usually granted for the duration of 1 to 3 years. To minors, it is usually granted until they reach the age of maturity.

Rights of asylum seekers include accommodation in Asylum Home or its unit, health care, job applications (after 9 months) and education.

Rights of persons with granted international protection include social care (the same as citizens’), accommodation (1 year in integration houses), health care, employment and work, education and learning of the language (300 hour course and additional 100 hour course).

Retour en haut

8 REFUGEE WELCOME SURVEY

The Refugees Welcome Index is based on a global survey of more than 27,000 people commissioned by Amnesty International and carried out by the internationally renowned strategy consultancy GlobeScan. The survey asked: “How closely would you personally accept people fleeing war or persecution?”

The results show that people are willing to go to astonishing lengths to make refugees welcome:

Globally, one person in 10 would take refugees into their home. The number rises to 46% in China, 29% in the UK and 20% in Greece, but was as low as 1% in Russia and Indonesia.

Globally, 32% said they would accept refugees in their neighbourhood, 47% in their city/town/village and 80% in their country.

Globally, only 17% said they would refuse refugees entry into their country. Only in one country, Russia, did more than a third of people say they would deny them access (61%).

Retour en haut

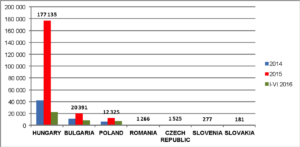

9 STATISTICS

Migrant residents

| Country | Population | Number of migrants | Percentage |

| Czech Republic | 10,5 milion | 467 500 (2015) | 4% |

| Poland | 38,5 milion | 211 900 (2015) | 1% |

| Hungary | 10 milion | 146 000 (2015) | 1,5% |

| Romania | 20 milion | 110 000 (2016) | 1% |

| Slovenia | 2 milion | 102 500 (2015) | 5% |

| Slovakia | 5,5 milion | 84 800 (2015) | 1,5% |

| Bulgaria | 7,3 milion | 25 200 (2016) | 1% |

Asylum seekers

Top 3 nationalities in 2015

Poland: Russian Federation (Chechnya) / Ukraine /Tajikistan

Czech republic: Ukraine / Syria / Cuba

Slovakia: Iraq / Afganistan / Ukraine

Hungary: Pakistan / Afghanistan / Iraq

Bulgaria: Afghanistan / Iraq / Syria

Romania: Syria / Iraq / Afghanistan

Slovenia: Afghanistan / Syria / Iraq